Estudo conclui que alta concentração do poluente ozônio eleva risco de morte por doença respiratória

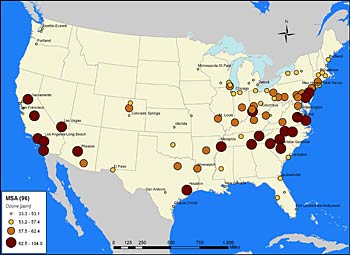

O mapa mostra as concentrações médias de ozônio no período de 1977-2000 em 96 regiões metropolitanas avaliadas no estudo.(Bernie Beckerman/UC Berkeley)

Pessoas que vivem em áreas com alta concentração do poluente ozônio têm 25 a 30 por cento mais chances de morrer de doenças pulmonares do que quem mora em lugares com ar mas puro, disseram pesquisadores na quarta-feira.

Michael Jerrett, da Universidade da Califórnia/Berkeley, e seus colegas acompanharam quase 500 mil pessoas nos Estados Unidos ao longo de 18 anos, e concluíram que o ozônio não tinha influência sobre as mortes por doença cardíaca, quando se levava em conta a poluição por material particulado. Matéria da Agência Reuters, com informações complementares do EcoDebate.

Já o ozônio, que no nível do solo é uma forma corrosiva de oxigênio e constitui o principal componente da poluição urbana, tinha um papel chave nas mortes por causas respiratórias.

“Agora sabemos que controlar o ozônio é benéfico não só para mitigar o aquecimento global, mas pode também ter benefícios em curto prazo na redução das mortes por causas respiratórias”, disse Jerrett em nota.

Os médicos há muito tempo sabem que o ozônio é nocivo. A exposição mesmo breve agrava os sintomas da asma e gera problemas respiratórios. Alertas sobre ozônio são comuns em grande parte dos Estados Unidos em dias quentes do verão.

O estudo [Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality], publicado na edição de quinta-feira da revista New England Journal of Medicine, mostra que a exposição prolongada aumenta a mortalidade, segundo Jerrett.

“É a primeira vez que conseguimos relacionar a exposição crônica ao ozônio, um dos poluentes mais difundidos do mundo, com o risco de morte”, disse ele.

Cerca de 7,7 milhões de pessoas morrem por ano de causas respiratórias no mundo, e a equipe relatou que elevar o nível de ozônio em 10 partes por bilhão já aumenta em 4 por cento a probabilidade de morte por problemas pulmonares.

Em altitudes estratosféricas, a camada de ozônio tem uma função positiva em proteger a Terra dos raios solares.

Matéria da Agência Reuters, no UOL Notícias, 11/03/2009 – 19h57.

Nota do EcoDebate: o estudo “Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality‘, publicado no New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 360:1085-1095, March 12, 2009, Number 11, apenas está disponível para assinantes. Abaixo transcrevemos o abstract e o press release do NYU Langone Medical Center / New York University School of Medicine :

Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality

Michael Jerrett, Ph.D., Richard T. Burnett, Ph.D., C. Arden Pope, III, Ph.D., Kazuhiko Ito, Ph.D., George Thurston, Sc.D., Daniel Krewski, Ph.D., Yuanli Shi, M.D., Eugenia Calle, Ph.D., and Michael Thun, M.D.

Background

Although many studies have linked elevations in tropospheric ozone to adverse health outcomes, the effect of long-term exposure to ozone on air pollution–related mortality remains uncertain. We examined the potential contribution of exposure to ozone to the risk of death from cardiopulmonary causes and specifically to death from respiratory causes.

Methods

Data from the study cohort of the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II were correlated with air-pollution data from 96 metropolitan statistical areas in the United States. Data were analyzed from 448,850 subjects, with 118,777 deaths in an 18-year follow-up period. Data on daily maximum ozone concentrations were obtained from April 1 to September 30 for the years 1977 through 2000. Data on concentrations of fine particulate matter (particles that are ?2.5 µm in aerodynamic diameter [PM2.5]) were obtained for the years 1999 and 2000. Associations between ozone concentrations and the risk of death were evaluated with the use of standard and multilevel Cox regression models.

Results

In single-pollutant models, increased concentrations of either PM2.5 or ozone were significantly associated with an increased risk of death from cardiopulmonary causes. In two-pollutant models, PM2.5 was associated with the risk of death from cardiovascular causes, whereas ozone was associated with the risk of death from respiratory causes. The estimated relative risk of death from respiratory causes that was associated with an increment in ozone concentration of 10 ppb was 1.040 (95% confidence interval, 1.010 to 1.067). The association of ozone with the risk of death from respiratory causes was insensitive to adjustment for confounders and to the type of statistical model used.

Conclusions

In this large study, we were not able to detect an effect of ozone on the risk of death from cardiovascular causes when the concentration of PM2.5 was taken into account. We did, however, demonstrate a significant increase in the risk of death from respiratory causes in association with an increase in ozone concentration.

Source Information

From the University of California, Berkeley (M.J.); Health Canada, Ottawa (R.T.B.); Brigham Young University, Provo, UT (C.A.P.); New York University School of Medicine, New York (K.I., G.T.); the University of Ottawa, Ottawa (D.K., Y.S.); and the American Cancer Society, Atlanta (E.C., M.T.).

Address reprint requests to Dr. Jerrett at the Division of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of California, 710 University Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720, or at jerrett{at}berkeley.edu.

Press Release: Study finds long-term ozone exposure raises the risk of dying from lung disease

NEW YORK, March 11, 2009 – Long-term exposure to elevated levels of ground ozone—a major constituent of smog—significantly raises the risk of dying from lung disease, according to a new nationwide study of cities that evaluated the impact of ozone on respiratory health over an 18-year period.

The study found that the risk of dying from respiratory disease is more than 30 percent greater in metropolitan areas with the highest ozone concentrations than in those with the lowest ozone concentrations.

Over the last decade, several nationwide studies have shown that long-term exposure to tiny particles of dust and soot in air pollution is a risk factor for death from heart and lung disease. However, it was unclear whether long-term exposure to ozone, a widespread pollutant in summertime haze, was linked to a higher risk of dying from lung disease itself.

The new study, published in the March 12 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, is the first nationwide population study on the long-term impact of ozone on human health, and the first to separate ozone’s effects from those of fine particulate matter, the tiny particles of pollutants emitted by factories, cars, and power plants.

“Many studies have shown that a high-ozone day leads to an increase in risk of acute health effects the next day, for example, asthma attacks and heart attacks,” says George D. Thurston, Sc.D. who directed the air pollution exposure assessment part of the study. “What this study says is that to protect the public’s health, we can’t just reduce the peaks, we must also reduce long-term, cumulative exposure.” Dr. Thurston is a professor in the Department of Environmental Medicine at NYU School of Medicine, a part of NYU Langone Medical Center.

Ozone in the upper atmosphere protects against harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. At ground level, ozone, or O3, forms when nitrogen dioxide from tailpipes, coal-fired power plants and other industries collides with oxygen in the presence of sunlight. Considered a secondary pollutant because it takes time to form, ozone tends to be higher in concentration in suburbs and rural areas downwind of cities. Fine particulate matter, a primary pollutant, is more prevalent at its source, in the inner city, along roadways and in industrial areas.

In concert with rising death rates from respiratory disease, “background levels of ozone have at least doubled since pre-industrial-revolution times,” says Michael Jerrett, Ph.D., associate professor, Division of Environmental Health Sciences, at the University of California, Berkeley, and the lead author of the new study.

The study analyzed data on some 450,000 people who were followed from 1982 to 2000 as part of an American Cancer Society study. Over that period 118,777 people in the study died. The data, which included cause of death, were linked to air pollution levels in 96 cities using advanced statistical modeling to control for individual risk factors, such as age, smoking status, body mass, and diet, as well as for regional differences among the study populations.

By statistically controlling for the other major component of smog—fine particulate matter, particles smaller than 2.5 microns—the researchers were able to tease out the cardiovascular impact of the pollutants and still see ozone’s effects on respiratory health.

Ozone data collected between 1977 and 2000 showed that California had both the city with the highest and the city with the lowest concentration of ozone pollution in the country. The researchers estimate that the risk of dying from respiratory causes rises 4 percent for every 10 parts-per-billion increase in exposure to ozone. Based on that result, Dr. Thurston says the city with the highest mean daily maximum ozone concentration over the 18-year period of the study, was Riverside (104 ppb). This long-term cumulative exposure corresponded to roughly a 50 percent increased risk of dying from lung disease compared to no exposure to the pollutant. Los Angeles ran a close second, with an estimated 43 percent increased risk.

Northeast cities were generally lower in ozone than California. In Washington, DC, and New York City, for example, the study results indicate a 27 and 25 percent increased risk of respiratory death, as a result of their respective long-term ozone exposures, says Dr. Thurston. The estimated increased risk from cumulative exposure in New York occurs even though New Yorkers breathe air that is nearly in compliance with the EPA’s present short-term ozone standard of 75 ppb, he says.

The lowest ozone concentration was seen in San Francisco (33 ppb long-term average daily maximum), which had an associated 14 percent increase in risk. San Francisco has low levels of ozone pollution because fog regularly blankets the city, which prevents the necessary photochemical reaction from occurring, says Dr. Jerrett. In addition, Dr. Thurston points out that the Los Angeles area, which has high levels, is located in a basin, which prevents the rapid dispersal and dilution of air pollution that occurs in San Francisco.

The EPA provides a list of counties in the United States, their present ozone concentrations, and their compliance status with regard to the current short-term ozone standard at the following URL: http://epa.gov/air/ozonepollution/pdfs/2008_03_design_values_2004_2006.pdf.

The present EPA air quality standards do not protect against the long-term cumulative effects of ozone exposures, but only address the health effects of short-term daily peaks in ozone exposure, says Dr. Thurston. Currently, the Environmental Protection Agency’s standard for short-term (8-hour) ozone exposure is 75 parts per billion, which exceeds the 60 ppb recommended by the EPA’s own scientific advisory group, the American Lung Association and more than a dozen other public health organizations. The EPA will be reviewing its ozone standard in the coming year.

“How do we lower the burden of disease?” queries Dr. Thurston. “Do we look only at only those affected by the highest days, or do we look at everyone’s exposure over the entire year? Since we all share the same air, paying attention to cumulative exposure shifts the whole exposure distribution for us all, and that’s where the health payoff is. A small reduction in everybody’s year-round risk benefits us all.”

###

The other co-authors of this study are: Kazuhiko Ito from the NYU School of Medicine; Arden Pope from Brigham Young University; Richard Burnett from Health Canada, the federal health department based in Ottawa; Daniel Krewski and Yuanli Shi from University of Ottawa; Michael Thun and the late Eugenia Calle from the American Cancer Society in Atlanta.

About NYU Langone Medical Center

Located in the heart of New York City, NYU Langone Medical Center is one of the nation’s premier centers of excellence in health care, biomedical research, and medical education. For over 167 years, NYU physicians and researchers have made countless contributions to the practice and science of health care. Today the Medical Center consists of NYU School of Medicine, including the Smilow Research Center, the Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine, and the Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences; the three hospitals of NYU Hospitals Center, Tisch Hospital, a 726-bed acute-care general hospital, Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, the first and largest facility of its kind, and NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases, a leader in musculoskeletal care; and such major programs as the NYU Cancer Institute, the NYU Child Study Center, and the Hassenfeld Children’s Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders.

[EcoDebate, 12/03/2009]

Inclusão na lista de distribuição do Boletim Diário do Portal EcoDebate

Caso queira ser incluído(a) na lista de distribuição de nosso boletim diário, basta que envie um e-mail para newsletter_ecodebate-subscribe@googlegroups.com . O seu e-mail será incluído e você receberá uma mensagem solicitando que confirme a inscrição.